Through the Loras Experience, you gain an insight into the interests and expertise of Loras faculty. Discover what makes the learning experience at Loras special as different faculty share their knowledge with you.

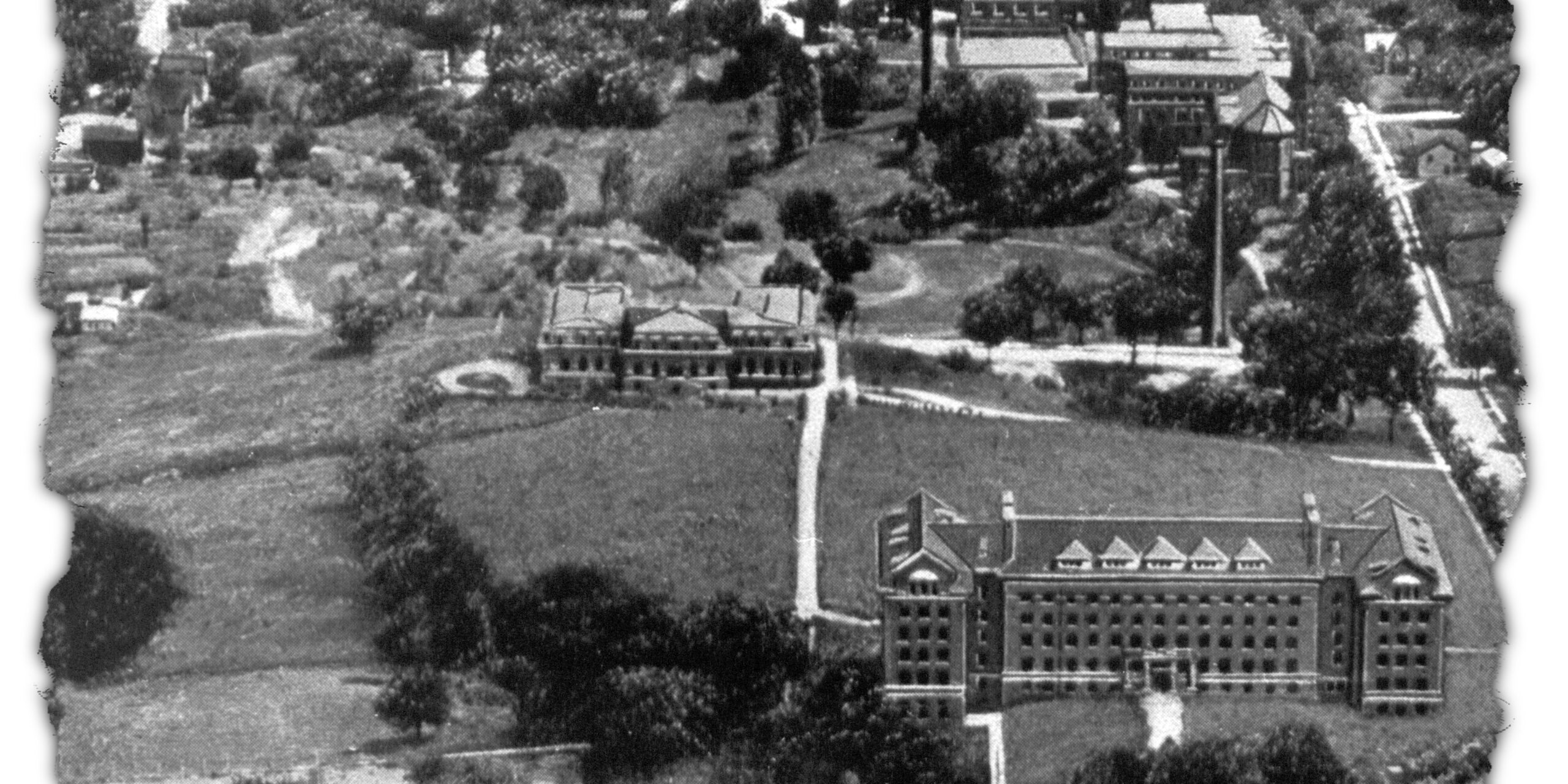

The Loras College Center for Dubuque History (CDH) preserves a unique artifact documenting the incidence of contagious disease in Dubuque between 1890 and 1924. City clerks recorded our city’s experience with the 1918 influenza epidemic in the leather-bound ledger now featuring a loose spine and yellowing pages. When I first encountered the book, I deemed it important because I could use it as a starting point for teaching research skills using local history. After engaging in an undergraduate-faculty research project each spring semester since 2016, I realize that through this project my students and I are recovering a lost episode of our community’s past and placing it into an international context. Beginning with digitizing and analyzing the Communicable Disease Book of Dubuque, students moved on to gathering news articles and obituaries from the Telegraph-Herald and Democrat-Times. City council records, city ordinances, city directories and hospital records added to our understanding. Because 104 young men enrolled in high school and college at our institution became infected, yearbooks, undergraduate bulletins, student publications and registrar office records provide insight into its impact on Loras College. In addition to creating a 1918 influenza archive at the CDH, the end goal of the project is to create an interactive website for community use. The information uncovered by students offers a lens through which to understand the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed 50 to 100 million people globally, yet quickly receded from memory. In the United States, the “Forgotten Epidemic” infected about one-quarter of the population and killed approximately 675,000 Americans between September 1918 and January 1919. Historians theorize that people chose to forget about the fear and sadness of these few months because they chose instead to celebrate the end of World War I. Trench warfare literally created the influenza pandemic, mutating a relatively minor H1N1 avian strain first recorded in Kansas in March 1918 into a more lethal virus. This second outbreak followed soldiers and sailors from European war zones around the world between August and November. Military vessels with infected men arrived in U.S. port cities and internal transportation networks carried these men to army and navy cantonments throughout the nation. Civilians working on these bases or interacting with enlisted men on furlough spread the infection into the general population. Influenza reached epidemic proportions on the East coast first and spread quickly in some cities due to the unlucky coincidence of massive parades held to raise war funds during the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive. Similarly, COVID-19 spread along global trade routes, but a very different populace brought the infection into various communities. Rather than enlisted men traveling by steamer and train, COVID-19 arrived on airplanes and cruise ships with wealthier and/or more politically powerful individuals engaged in international business, trade or tourism.

My students and I have not discovered exactly who brought influenza to Dubuque. The Great Lakes Naval Training Station, near Chicago, reported the arrival of the disease on September 17 and the first local “boy” to die during the epidemic perished there on September 19. Other nearby army cantonments in Rockford, Illinois and Des Moines, Iowa reported hundreds of ill soldiers by September 23 and September 30, respectively. A physician reported the earliest date of infection in Dubuque as September 24, but the virus probably arrived earlier. According to the Telegraph-Herald on September 27, thirty-eight orphans and five attendants at the Hillcrest Baby Fold suffered from flu. The ambulance service found itself transporting 12 to 18 patients to the hospital a day during the first week of October. By the time fourteen doctors filed the first cases of infectious disease with the City Clerk on October 7 and 8, they were treating 265 patients.

Officially, 2039 individuals contracted influenza and 46 died (a mortality rate of 2.3%). However, in the chaos of that month and in the uncertainty of whether or not a person had influenza or a “bad cold,” physicians underreported infection and death rates. This sounds familiar because of the current difficultly of trying to get an accurate count of the number of individuals with COVID-19 due to the unavailability of testing and asymptomatic carriers. Influenza killed individuals outright, but more died of pneumonia, which also made record keeping challenging. By analyzing obituaries, my students discovered the death of 88 additional Dubuquers. The occurrence of at least 134 deaths attributable to influenza places the number of total cases in Dubuque closer to 5826 (14.9% of the population). Although COVID-19 most significantly afflicts the elderly and those with existing health conditions, influenza proved most virulent in men and women between the ages of 15 and 45.

The local Board of Health met on October 11 and initiated a citywide quarantine the next day closing schools, churches, theaters and other places of public assembly. One week later, at the order of the State of Iowa, Mayor Saul mandated that citizens avoid all social gatherings, including card parties, house to house visits and funerals. Although businesses did not close, extra streetcars ran to avoid crowding, folks wore masks while caring for the sick, and people regularly learned how to avoid spreading the infection thru public health announcements. Nursing care proved more important than the talents of a physician, but because of the war, Dubuque faced a nursing shortage. Through the Red Cross and the Visiting Nurse Association, women volunteered to assist the households where entire families suffered with illness or ill parents could not care for their children. The newspapers published guidelines instructing how to nurse loved ones in the home, while the Sisters of Charity made nutritious broth and distributed it to ill families. In 1918, Dubuque citizens helped one another through the crisis but also relied on government to establish guidelines. Nationally, communities faired better when governments acted quickly to establish quarantines and discourage public assembly. They also needed to maintain restrictions long enough to curb transmission. Localities that ended social distancing too early, such as Des Moines, suffered a resurgence of the epidemic and needed to re-impose controls. Dubuque in 1918 only experienced about three weeks of quarantine because the virus infected many before the initiation of the closure order and gathering ban. Dubuque in 2020 will require a much longer period of social isolation because social distancing began just as the infection reached our community.

Authorities lifted the quarantine on November 4, but asked citizens to practice caution and protect one another by self-quarantining. The next day, a Telegraph Herald editorial stressed the importance of anyone with symptoms of the flu to avoid being a carrier and inadvertently “scattering death among their friends and associates.” We, today, must internalize this same message. If fifty percent of those with COVID-19 are asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic, each of us must assume we are a carrier and take proper precautions. Isolate your household from others, practice social distancing and wear a mask in places where you cannot keep six feet between you and others. In an editorial on the eve of the local outbreak (September 26), the Telegraph Herald admonished readers to “Keep Germs to Yourself.” The paper printed the following “familiar hygienic couplet” without knowing how the epidemic would affect their community. Similarly, we cannot know the ramifications of the current pandemic, but we can, “Cover up, each cough and sneeze. If you don’t, you’ll spread disease.”

To learn more about the global influenza epidemic, Susan Kingsley Kent’s The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919 (Bedford/St. Martins, 2017) provides an accessible overview of the scholarship in a well-written introduction and she brings together primary sources from around the world to illustrate the extent of the impact. The interactive Influenza Encyclopedia by the University of Michigan Center of the History of Medicine (https://www.influenzaarchive.org/) provides summative information on 50 cities, including Des Moines, and newspaper articles for each city.